The silence was noticeable. Several times, when I told people we were taking a holiday in Leeds, the response was slow coming. “Well, I’m sure you’ll have a lovely time… ”

We, however, were reasonably confident in expecting more from the city at the heart of Britain’s fourth-largest conurbation. We have been working our way through visits to all of the country’s big cities, to see what these places, still often despised in popular opinion, are really like today after several decades of urban renewal. In only one case were we disappointed – and Leeds was the last big place on the list. I think it is fair to say that after several decades in the doldrums, Britain’s city centres are now generally worthy of the nation’s civic pride.

It was about 25 years since I had last visited Leeds, briefly, for a friend’s wedding, so I had few recollections of the city – but I knew that it had stolen a march even on Manchester in being quick out of the blocks of urban renewal. Even some of the new waterside developments are nearing thirty years old. It is now the largest financial and legal centre in England, outside London. Its high productivity has generated income whose consequences have had time to bed in, and have had a lasting effect on the city. There is still quite a lot to do when it comes to the areas just outside the city centre – but we observed the early stages in the creation of a new city park, alongside which, in a decade or so, will eventually rise the new High Speed 2 rail station, thus extending the already impressive new districts to the south of the River Aire.

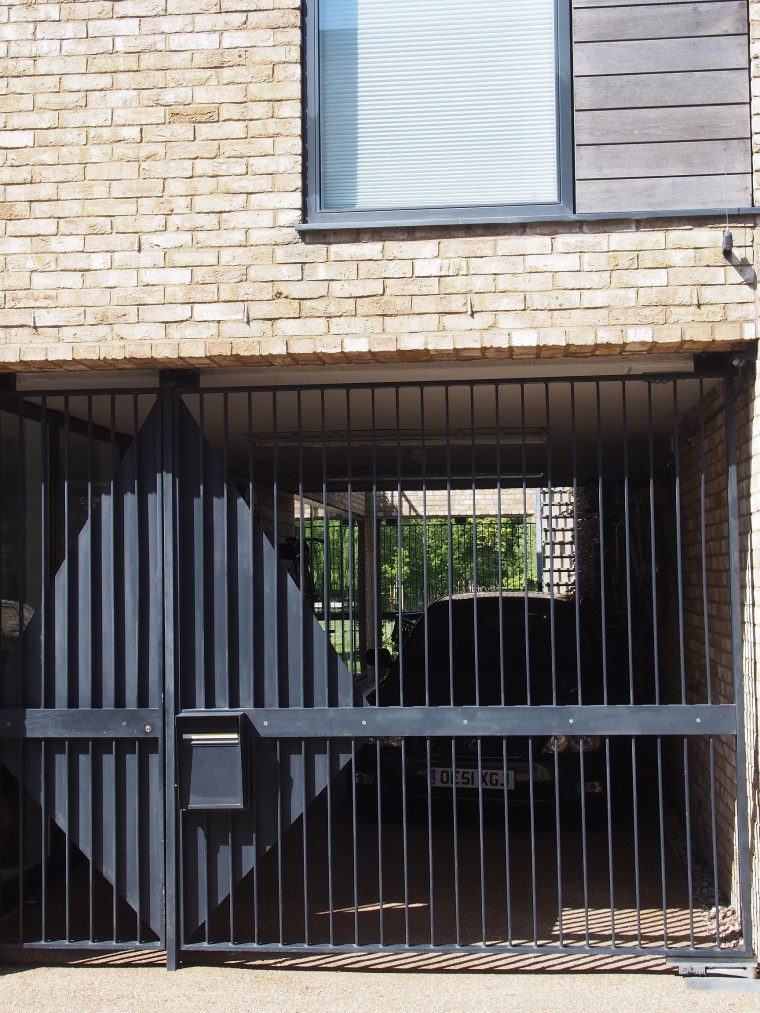

For once, I had been organised, and booked our visit several months in advance. As a result, we had a room in a 42 The Calls Hotel, an early conversion of a grain warehouse into an attractive hotel, even if its early-nineties decor is now in need of a lift (forthcoming, we gather). A room upgrade saw us installed with a river view, and the roof trusses and machinery of the former hoists to look up at in bed each evening. The rest of the building is an attractive blend of Victorian beams and pillars and modern interventions.

The area around the former wharves on the River Aire is now redolent of similar dockland-style schemes across the country, but no less interesting for that. The backstreets just to the north seem to be doing a good impression of Shoreditch or Hoxton in London, with many creative businesses and bearded types in evidence… Edgy – but just sufficiently so.

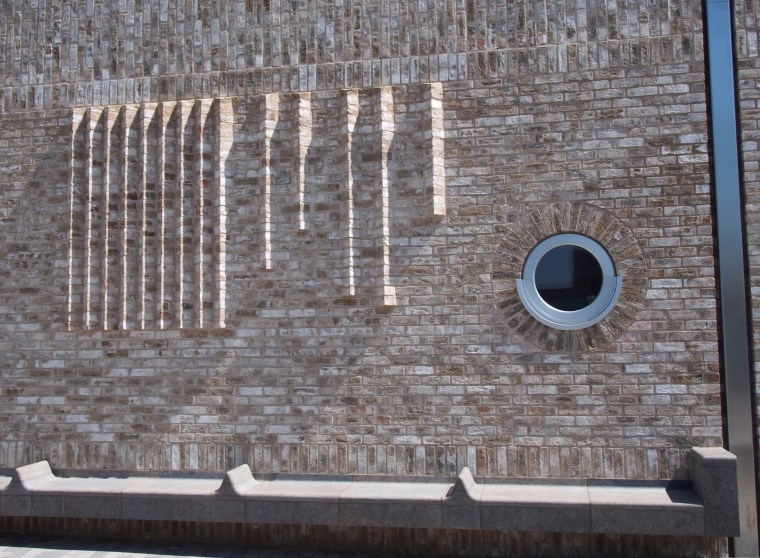

In fact, that is a good summary of the rest of the city, which has cleaned and restored many of its fine Victorian buildings, while making some appealing modern interventions and reinterpretations. The city has not been ‘over-cleaned’ – or perhaps the process has now been going on for long enough that the patina of reality is re-settling. Some rejuvenated places can feel just too pristine…

Much of the centre has been pedestrianised, with a number of new arcades being added to the very fine Victorian ones for which the city is known. As a retail centre, it now ranks with the best in the country, having Harvey Nichols as well as a large new ‘statement’ John Lewis. These have been the anchors around which many lesser known brands and a fair number of independents have clustered.

The city centre is a pleasant place to walk around, though I gather Friday evenings can still be “interesting”… There is an ornate Victorian indoor market, while the beautiful Corn Exchange now hosts a selection of esoteric independents.

Leeds has a lot to offer culturally too, with Opera North being homed here, as well as the Yorkshire Playhouse repertory theatre. Unfortunately, there was a lull in the programme during the days of our stay. The visual arts are perhaps slightly less well represented; the city Art Gallery is not on the scale of that in Manchester or Birmingham, though it does hold a significant collection of 20th Century art. Unfortunately this too was largely closed in preparation for the forthcoming Yorkshire Sculpture Festival – as was the Tetley Contemporary Arts Centre. Sculpture is perhaps the one visual art that bucks the trend: West Yorkshire has become something of a centre for it, on the back of the area’s associations with Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth (in nearby Wakefield), together with the well-regarded Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

We still find that many British towns and cities’ Achilles’ Heel is their eateries. Leeds does have Michelin starred restaurants – but for more ordinary mortals, the choice seems to be very largely restricted to the usual chain suspects. We try to escape these wherever we can. On our first night, we found a well-reviewed Italian not far from our hotel in another nicely-restored warehouse near the river. Unfortunately, the food was ordinary to say the least; we are not fastidious, but we do know our Italian food, and we can do better than this at home. More indicative, if this is considered locally to be outstanding, then expectations cannot be very high… Much renovation of British cities has found inspiration from the continent – and while there are now some very pleasing public spaces and architecture, it is a shame that the regular gastronomic offerings still mostly don’t come near our experiences of a place, for example, like Lille – let alone those further south.

We were able to see most of central Leeds in a day – it is fairly compact and easily walkable. The redeveloped areas along the river are extensive and attractive, though the main museum offering – the national Royal Armouries Museum was not really our cup of tea. Interesting building though.

On our second day, we travelled out of the city to some of the smaller places nearby – of which more another time.

As expected, Leeds proved to be a very successful choice for a short city break. It has a big-city feel without being overwhelming, and has made very successful use of its assets to emerge as another fine British city, whatever lagging public opinion might still be thinking. We’ll be back.